CASE STUDY:

Our Time Together

At Hugh Gilroy Neighborhood Senior Center in Weeksville, Brooklyn, participants in the SU-CASA weaving class, called Our Time Together, took to it so well that the teaching artist, Jamie Boyle, had to hustle to keep up. Boyle credits the center director at the time, Leishanna Lawrence, for knowing her community well and requesting a program they would like — even if, at first, some were skeptical of their ability to weave. Lawrence also promoted it well, with a lot of announcements.

Boyle had 11 people in her first class, and the class grew as they recruited more friends, she said — “once it was deemed fun in the room.” While she had planned a course of sequential learning, the enthusiastic participants took over and treated it as more of a creative activity than a class, even as they grabbed up new ideas. “I view that as a failure and a success,” she said.

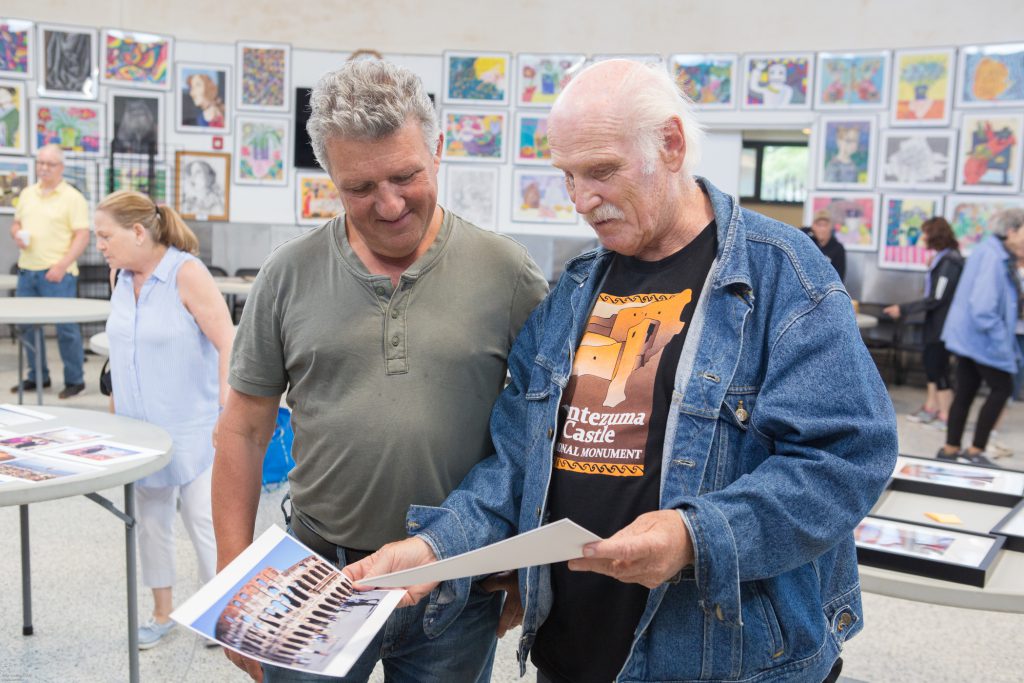

Boyle encouraged participants to see their work as art by bringing a frame to class and putting the finished pieces in the frame. She also tried to cultivate a feeling of what an artist’s studio is like. At the culminating exhibition, the artists displayed 61 weavings. Rather than bask in their glory, they wanted to spend that time weaving more. But after someone took the first photo of a weaver with her art, Boyle said, “pride swelled.”

SU-CASA is a phenomenal public investment. By funding five programs in each of NYC’s 51 Council districts, SU-CASA makes arts opportunities available in neighborhoods all across the city. The city’s extensive senior center system provides a built-in way to accommodate arts programming everywhere. Yet more attention is needed to address inequities in resources at different centers.

Evidence

Visits to senior centers with SU-CASA programs demonstrated that some have greater capacity, in terms of staff and/or facilities, than others.

- Some centers have dedicated art studios of various kinds; others have only one or two rooms to host all their activities. For example, the singing class at one center was held in a dedicated music room, while the singing class at another center was in a cramped area at one end of the main lunch and activity room, next to the restrooms and maintenance closets, because that’s where the piano was.

- Some centers have rich arts and learning programs in addition to the SU-CASA class or classes, while others have only the SU-CASA program, so they have arts programming for only a few months of the year. It stands to reason that the senior center staff and volunteers have more built-in resources and experience with running effective arts programming in centers where they do a lot of it.

- And, at the same time, centers with a lot of arts programming have cultivated an audience for that programming — older adults learn to embrace the opportunity — while older adults at centers with occasional and sporadic programming attend the center for other reasons, with arts programming appearing as an unexpected bonus.

- Centers with a lot of arts experience:

- are aware of the annual SU-CASA process and how to request specific programs for their center,

- have had the opportunity to learn more about what programs their members are interested in,

- know how to market culminating events, and

- are able to market effectively to repeat customers and those who have attended culminating events.

- Centers with fewer resources do not have these capacities. Although the geographic dispersal of SU-CASA is a benefit, success begets success. It also stands to reason that those centers without the needed capacity may be located in areas with the lowest amount of resources, and therefore where art could have the greatest impact.

- The City Council, DFTA, and DCLA do a remarkable job of matching the right artists and programs to NYC’s very diverse senior centers — most of the time. Every year, however, there are linguistic, project, and infrastructure mismatches (for example, a digital photographer in a center with no computers; clay in a center with no kiln; teaching artists and students with no language in common).

These patterns are apparent in the NYC arts world more broadly.

- While every neighborhood has a cultural scene, arts resources are far greater in Manhattan below 125th Street and neighborhoods near downtown Brooklyn than in the rest of the city: “The dominant pattern is one of privilege generating more privilege” (Stern & Seifert, 2017, p. VI-6).

- Yet research suggests that cultural resources may carry more bang for the buck in terms of social well-being in lower-income neighborhoods, where they promote social connection and therefore social capital, than in higher-income neighborhoods where residents have greater economic resources (Stern & Seifert, 2017).